Why It Costs More And Takes Longer to Build Housing for the Homeless in LA

If you’ve read one of my previous posts on the housing crisis for the chronic homeless in Los Angeles, I appreciate your exploring the topic with me as I attempt to educate myself on the complex issues surrounding chronic homelessness and its solutions.

There was a time when I was of the mind that you could not force help on those enduring persistent homelessness. What I’ve come to learn – and perhaps you’ve learned with me – is that Housing First programs across the US have been very successful in reducing chronic homelessness.

The critical component to the success of any Housing First program is, of course, to have available housing.

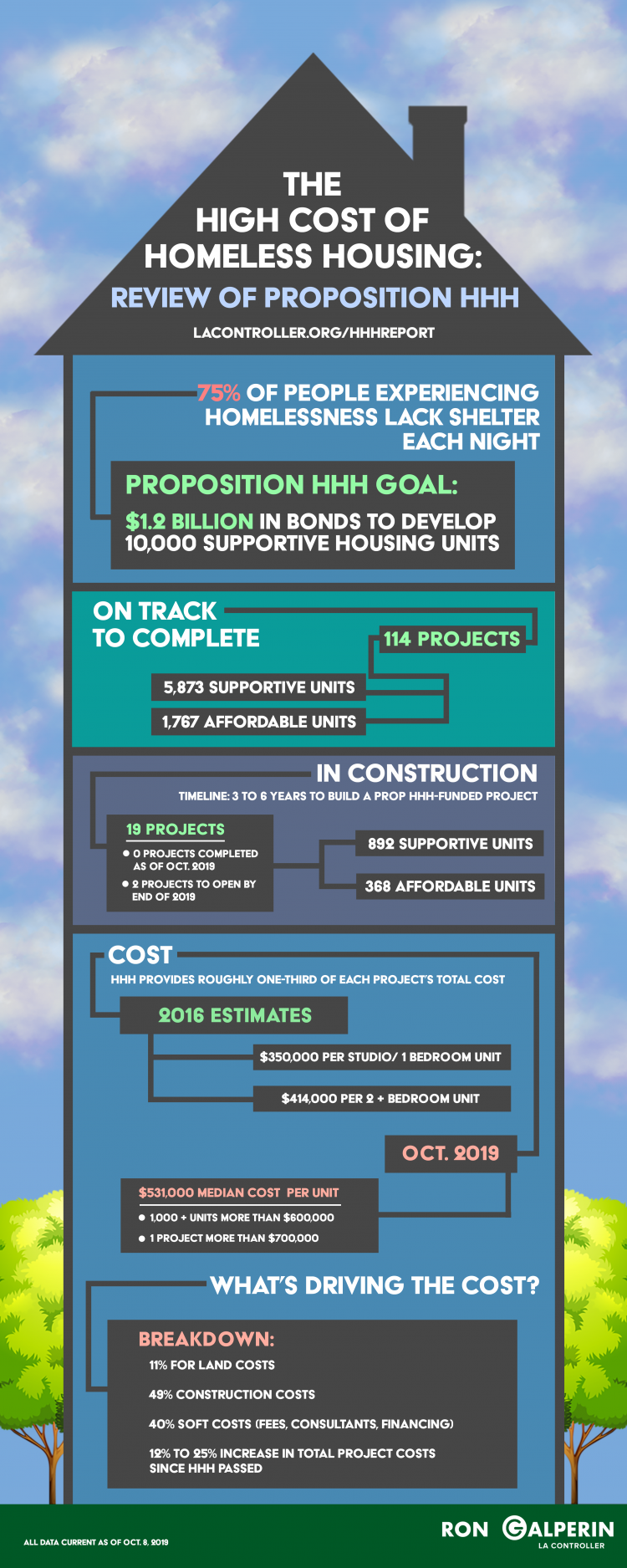

Los Angeles has decided to rely heavily on new construction to provide housing for its exploding chronic homeless population. As previously discussed, in 2016 the voters of LA County approved a $1.2 billion bond initiative to build 10,000 new housing units for the homeless.

Unfortunately, three years later the first 100 units are just now coming online at an average cost of $531,000 per apartment, well over the original estimates of $350,000 to $414,000 a unit and substantially later than anticipated.

To put this in perspective, of the 58,936 homeless population count in 2019, 15,855 were considered chronically homeless, an increase of 2,296 from the previous year. At the current pace of completion, the $1.2 billion dollars in taxpayer money won’t keep up with the increase in chronic homelessness in LA County.

So the question is, why does it take so long to build homeless housing and why does it cost so much?

The cost in time and money to build new housing for the homeless in Los Angeles

In October of last year (2019) the Los Angeles city Controller, Ron Galperin, released a status report on the progress of Proposition HHH that authorized $1.2 billion in public financing to build 10,000 units of housing for the homeless. Galperin’s report highlighted that:

- Many HHH-funded units will cost more than the median sale price of a market-rate condo in the City and a single-family home in the County.

- 35 to 40 percent of costs for the HHH housing are so-called “soft costs” (development fees, consultants, financing, environmental compliance, etc.) compared to just 11 percent for actual land costs

- As of the date of the report, only 19 projects are in construction and zero HHH-funded units are open. (As of January, 2020 there are a bit over 100 units that are habitable.)

- The estimated number of units constructed from this funding will likely decline to 7,000 units from an originally estimated 10,000 units

When you read Controller Galperin’s report on the lack of progress, it’s absolutely maddening. Public and private interests and goals – often separate from the actual construction of housing for the homeless – are layered on to each project, adding cost and extending timelines.

The Controller does an excellent job of summarizing the reasons for the high costs and delays in his report. I’ve copied those reasons here:

- Funding complexity – In addition to

Proposition HHH funds, developers typically assemble several loans and grants

to fully fund a project. On average, each development approved by the City had

seven funding sources (including Proposition HHH). The complexity of this model

adds costs and delays housing production because each funding source has its

own set of policy priorities and approval timelines.

- Regulatory framework – Projects built using

public subsidies typically include requirements that can increase soft costs

due to the need for additional consulting services to address legal or

accounting issues. In addition, projects built using Proposition HHH funds can

incur higher construction costs due to accessibility requirements – each

project must include at least 4 percent of units set aside for persons with

sensory impairments and 10 percent of units for persons with mobility

impairments. Developers, general contractors, and subcontractors may instead

choose to pursue market-rate projects that yield greater profits, thereby

shrinking the overall pool of available firms and driving up costs.

- Limited pool of eligible developers –

Proposition HHH regulations require lead developers to demonstrate a history of

building and managing supportive housing projects. This reduces the overall

level of risk and increases the likelihood that projects funded by the City are

successful. However, this requirement can also impede competition and prevent

developers from outside the traditional supportive housing community – who may

bring new and innovative ideas – from participating.

- Labor costs – Projects built using Proposition HHH funds are subject to State Prevailing Wage Requirements. In addition, housing developments of 65 or more units must include a project labor agreement that promotes the hiring and continued employment of local residents, including those that may be classified as transitional or disadvantaged workers.

As you read through Galperin’s list, none of the items jump out as especially egregious in and of themselves. Who would be opposed to greater accessibility for the physically impaired? Who wouldn’t want local residents to be hired to do the construction? It makes sense to only allow developers with experience in building supportive housing, doesn’t it?

When you tally the cumulative weight of these hurdles, it becomes obvious why it took three years and cost over $530,000 a unit to complete the first Prop. HHH housing units. We shouldn’t be surprised that it took so long and cost so much. We should be thankful that it didn’t take longer and cost much, much more.

Is the lack of housing for the chronically homeless an emergency, or not?

In 2019, over 1,000 people with no permanent residence died on the streets of Los Angeles County. The ultimate causes of death were varied, but who would dispute that being without permanent shelter likely contributed to the deaths of each and every person?

If the plight of the chronic homeless is a medical and humanitarian emergency, then we must treat the cure as an emergency as well.

The disease of being chronically homelessness has a cure, and it’s housing. With the clock ticking and people dying, let’s hit the pause button on anything not directly related to homeless housing construction or rehab until the tide has turned and the number of units coming online each year exceeds the growth of the chronically homeless population.

That’s right. Let’s put a pause on the requirement that solar panels be a part of every newly constructed residential building. Let’s waive the requirement for a minimum amount of new off-street parking spots. We will put a hold on the prevailing wage requirements for tradesmen that pushes hourly wages to $36. Let’s provide an exemption to the governmental red tape that is often used by special interest groups to slow down or halt new construction.

A.B. 1197 and The California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA)

With great fanfare, members of the California State Assembly from Los Angeles County celebrated the passage of A.B. 1197 in October of 2019 – three years after voters of LA County approved the expenditure of $1.2 billion to create 10,000 units of housing for the homeless.

What did A.B. 1197 do? It effectively lifted the requirements set by the mother of all California construction laws, The California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), for new homeless housing construction in Los Angeles for a period of 5 years.

State Assembly Member Miguel Santiago, whose district includes Skid Row in downtown L.A. proclaimed,

“A.B. 1197 streamlining will shave between a year and eighteen months off housing project timelines, which could save $2 billion through 2025”

Huh?

By providing and exemption to CEQA requirements homeless housing can be accelerated by twelve to eighteen months and at a lower cost? What exactly is the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), and how can it add so much time and cost to multi-unit residential housing construction?

That’s the topic of my next post! To pique your interest, here’s a quotation from a former Director of the California Department of Housing and Community Development concerning CEQA:

Timothy Coyle, a former director of the California Department of Housing and Community Development, has seen CEQA’s implementation from the inside and concludes that (CEQA) is “the mother of all government-sponsored obstacles to development.” Business rivals, environmental activists, and neighborhood groups use CEQA to delay, and whenever possible, stop development projects.

As a real estate investor and developer new to California, you can color me interested! If you’re a Chicago-based contractor, investor or property manager, you may want to learn more in anticipation of similar laws working their way into Illinois.