The Homeless Crisis in LA, A Chicagoan’s Perspective

Before Robin and I moved to Los Angeles we had seen the reports of homeless encampments in LA. The pictures of tents on sidewalks didn’t much phase us, as we’re also concerned about Chicago’s own homeless population. How different, we thought, could it be?

Let me put it this way. The unsheltered homeless in Los Angeles is larger and more expansive on a scale that’s hard to comprehend. The photos below were taken close to our home in Studio City and representative of what you can see in most parts of Los Angeles.

The hours I shared with the good people at Franciscan Outreach, a homeless shelter in Chicago, opened my eyes to the depth and complexity of the homeless problem. I learned from the staff that the men and women who found temporary shelter and food at Franciscan had widely different short and long-term physical, mental and economic needs. To hear it all was overwhelming at times.

Unfortunately, it’s precisely the complexity of the homelessness that makes the issue ripe for demagoguery.

Homelessness is the cudgel that some on the far left and far right use to beat each other with righteous indignation. On the Far Right the homeless plight in cities like Seattle is used as proof that Progressives fail miserably when given power, that the Left’s solution to everything is to spend money and to demonize those who disagree with them.

On the Far Left, the mere existence of homelessness is proof that capitalism is evil, that Americans are uncaring, and that the anyone who doesn’t ascribe to this world view is a racist, bigoted, and unredeemable.

Fingers are pointed. Political points are scored. Positions are hardened. The problem is not solved. The people are not served. As I think of my friends of all persuasions, every one of them would insist the we can do better.

What is The Scope of the Homeless Challenge?

The first step is understanding the homeless situation in any city is to find reliably sourced and reported data. Competing governmental organizations and advocacy programs define homelessness in different ways, often playing to their own narrative. For example, the Chicago Department of Family and Supportive services reported 5,450 people as being homeless in 2018. For the same year, the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless estimated that 80,000 people were homeless. How could one possibly explain the discrepancy of 74,550 people?

As Julie Dworkin of the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless explained it to the Chicago Tribune, “Theirs is a point in time, ours is year-round,” Her organization estimates that there are 80,000 homeless in the city, including those who are “doubled-up,” meaning they live with another person but have no home of their own. It’s a definition that differs from the one used by the city, which counts homeless people following guidelines set by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

No one has bad intentions here, but you can’t solve a problem if you can’t accurately define its scope.

Defining the Three Major Homeless Subgroups

Understanding that the homeless population is as diverse as the broader population helped me to wrap my head around the problem in a way that makes the challenge seem less daunting.

The most widely accepted definition of the homeless population is that offered by the Department of Housing and Urban Development which, not coincidentally, controls millions in funding for homeless programs. According to the HUD and as summarized by Partners Ending Homelessness, the homeless can be organized into three general categories.

Situational (Temporary): An individual is considered to be experiencing situational homelessness when they are facing some sort of housing, health care, financial, or job loss crisis. When homeless services are provided, these individuals usually are able to locate and obtain another stable housing situation.

Episodic: An individual is considered to experiencing episodic homelessness when they are having recurrent problems with housing. Often these individuals have seasonal/minimum wage income or sporadic domestic situations that affect stable housing.

Chronic: Chronic homelessness, as summarized by the National Alliance to End Homelessness, is used to describe “people who have experienced homelessness for at least a year — or repeatedly — while struggling with a disabling condition such as a serious mental illness, substance use disorder, or physical disability.”

At some point in our lives we’ve probably known someone or have ourselves been in a situational homeless condition. Perhaps you had a friend who was recently divorced, or who fled an abusive relationship and you housed them for a few weeks. Situational homelessness could also include a relative who moved into your home because of a lost job, or recent arrival into the country. These are all examples of the situationally homeless. Across the country, the situationally homeless are estimated at 75% of the total homeless population at any given point in time.

The episodic homeless, as described by HUD, includes those who might be considered to have, “fairly disadvantaged lives, which leaves them at constant risk of becoming homeless. Among individuals in this group, jobs are less stable, housing costs consume a higher percentage of the household budget, and they have little or no financial buffers against emergencies. As a result, this group experiences periodic episodes of homelessness, but generally for short periods of time.” This group includes a percentage with substance abuse problems, medical conditions, mental illness, criminal records or other challenges that lead to a higher level of financial insecurity. It’s estimated that 10% of the homeless population is episodically homeless, according to Lloyd Pendleton, a homeless expert who lead Utah’s state-wide homeless program. (In a future post I’ll discuss how affordable housing can play a leading role in solving episodic homelessness.)

The final subgroup of the homeless population is the chronically homeless. Here’s a clinical description I found on the Health and Human Services website.

(The chronic homeless) often have complex physical, mental, and substance use conditions that can only be ameliorated if they have a safe, stable, and secure living environment. Their homelessness may exacerbate health difficulties, making it increasingly unlikely that they can get back into housing on their own. Many people who experience chronic homelessness are not effectively engaged in treatment or ongoing care for their chronic health conditions, mental health or substance use disorders. They may be distrustful of treatment systems or mainstream health care providers, and they may find it difficult to access care or participate in treatment programs because they are focused on meeting other priorities such as finding food or shelter.

Further, many people who experience chronic homelessness make frequent and avoidable use of emergency rooms and inpatient hospital treatment.4

The chronic homeless typically make up around 15% of the entire homeless population nationwide. In Los Angeles County, the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority estimates that 28% of the homeless can be described as chronically homeless.

Why Are There So Many Chronically Homeless on The Streets of LA?

The higher percentage of chronically homeless in LA County helps to explain some of the massive scale of the homeless encampments you see, but it doesn’t explain it all.

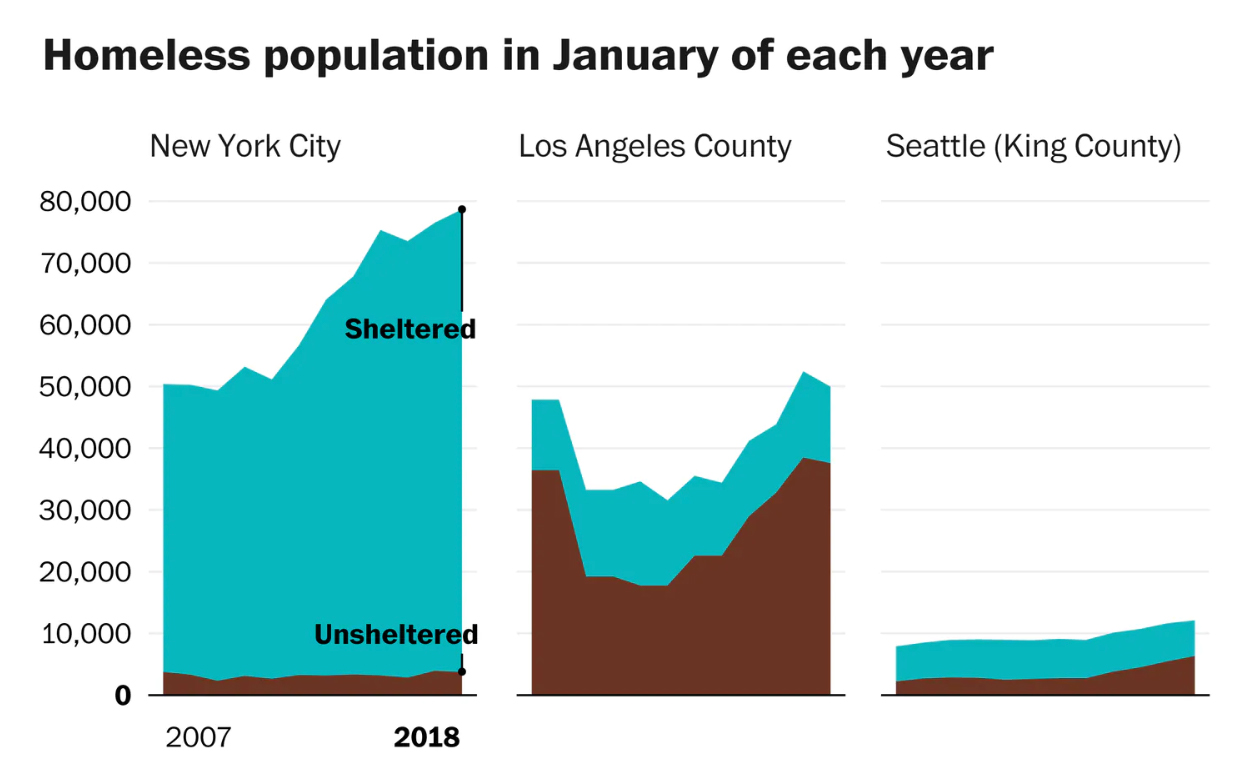

Here’s a graphic that compares New York City’s much larger homeless population, and the percentage that are sheltered, with Los Angeles’s sheltered and non-sheltered population.

The difference is stunning.

How is it possible that New York City has a homeless population substantially greater than that of Los Angeles, but has a far lower percentage of homeless people living on the streets? The wage and cost of living is similar in the two metropolitan areas. The rental housing prices in New York are actually higher than Los Angeles.

I’m still learning the right questions to ask. In the coming weeks I’ll provide a second blog post that might shed some light on why Los Angeles has such a large number of unsheltered homeless when compared to New York, what LA might learn from New York, and what real estate investors and developers could do to help solve the challenges of the chronically homeless and unsheltered.

For the time being, I’ll leave you with a very brief video that offers a real, substantive reason for hope. The video describes a program pioneered in New York City in the 1990’s that has come to be known as Housing First. Housing First is one of the primary reasons that nearly 90% of the chronically homeless are sheltered in New York City.

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer, but I’m discovering programs that have and will continue to help to solve the challenges of the chronically homeless among us. There’s reason to be hopeful if we can open our hearts, our eyes, and most importantly, our analytic, problem-solving minds.